Abstract – Exploring Calling

This study explores the concept of calling at work. It begins by looking at the definition of a calling, reflecting on motivation at work, the religious background of the concept of calling and the constituent parts of a calling: inner drive in a particular direction, the prosocial contribution and alignment with one’s strengths or issues one feels are important.

Career change and behavioural models are explored to understand a sense of calling. Measurement scales are also reviewed to identify those who might benefit from following their calling, how they are motivated and the need for intrinsic meaning. The study reviews the benefits of following a calling, the challenges individuals face, and the techniques scholars recommend in its pursuit.

This study aims to research the antecedents to mid-career professionals following a calling and explore how their life experiences have influenced decisions.

Exploring Calling – Keywords: meaning at work, calling, motivation, prosocial, values, strengths, exploring calling, psychology of calling.

Introduction – Exploring Calling

What is a calling?

To define the term calling, it is useful to contrast it to a Job or Career. Amy Wrzeniewski and colleagues, in their much-referenced paper, suggested that people see their work as either a Job, Career or Calling. A job is primarily for the money; a career offers progression, recognition and status, whereas a calling is fulfilling for the work itself and benefits society (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997).

Due to the increasing importance of work in people’s lives and their ability to reach their goals in the workplace, people look at work as a source of personal identity and a source of meaning (Cardador & Caza, 2012). Echoing Wrzesniewski (1997),

“Many workers want their work to be more than merely a source of income (a job) or an avenue for advancement and accomplishment (a career). Instead, individuals seek their work to provide intrinsic meaning and an opportunity to make a difference.” (Cardador & Caza, 2012, Page 1).

Steger & Dik (2009) take this a step further and suggest that deriving meaning from life experiences is essential for psychological health; given that we spend of third of our life at work, it makes

sense to address meaning whilst at work. Job, Career and Calling are good concepts, but it would be unwise to be too strict with definitions as some people might find their ‘job’ very intrinsically rewarding and a ‘calling’ might not be enjoyable (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997).

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

People following a calling are motivated by altruistic motives and the pursuit of intrinsic rewards, as opposed to extrinsic rewards or recognition (Ahn et al., 2017). Work driven by intrinsic motivation is a labour of love; people find the work interesting and can reach states of flow, compared to extrinsic motivation, when income, recognition and status are key drivers (Amabile et al., 1994). People who are driven by prestige, job titles, power and making lots of money are less likely to view their career as a calling (Dik & Duffy, 2009).

A meta-analysis of twenty years of research into the concept of calling suggested that people do not make a trade-off between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. It found that people driven by a calling are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated but slightly less extrinsically (Dobrow Riza et al., 2019). Whether a role is a ‘calling’ is in the eye of the beholder and not based on a specific vocation. One man’s job to pay the bills is another man’s calling. Research suggests roughly equal amounts of participants feel that work is a job, career or calling within participants with the same job title (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997).

A calling “emphasises action, a convergence of ourselves and a pro-social intention” (Elangovan et al., 2010, p. 428). Convergence of self is defined as what someone would like to do, should do, and actually does align. The absence of this convergence harms the self – which we will return to later in this paper. Regarding action, it is argued that each individual has a moral imperative to pursue one’s calling and duty to apply one’s talents for the benefit of society (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009) as well as the stamina and focus required to complete the mission (Hagmaier & Abele, 2012). It should also be noted that a calling is not something to be defined and resolved, but it is more of a feeling of general direction, and people may experience several callings on their journey (Dik & Duffy, 2009) (Elangovan et al., 2010).

The concepts of purpose and meaning at work are linked closely to the concept of calling and personal drive. Work purpose is when a role has meaning to the individual and consequences beyond the self. Meaningfulness is when a role helps someone make sense of their place in the world (Dik & Duffy, 2009).

Secular vs Religious Definitions of Calling

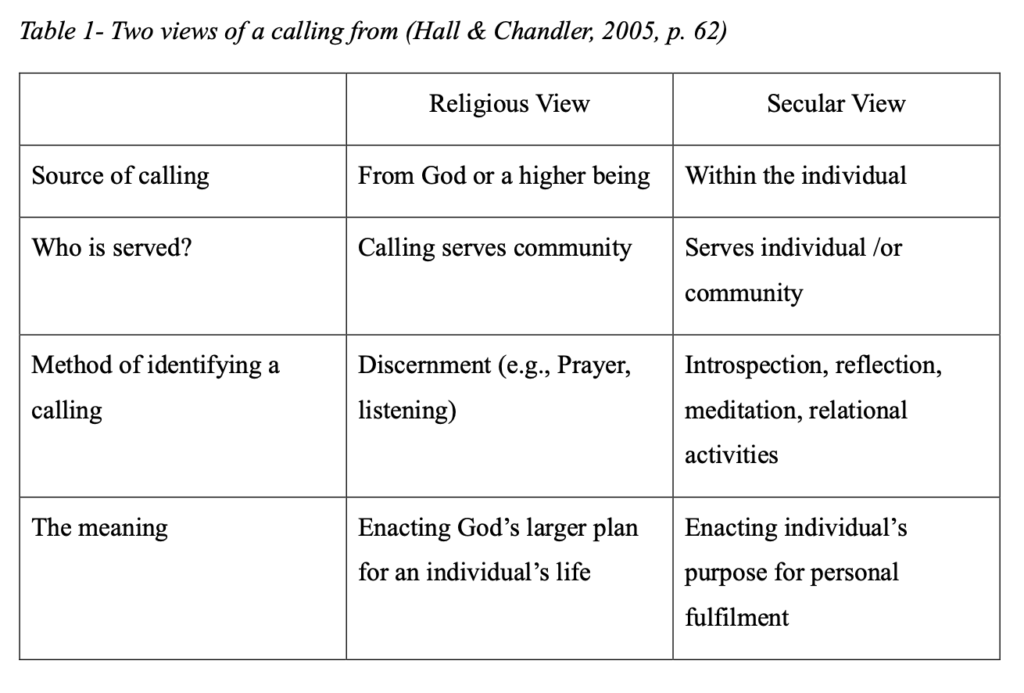

The word calling has religious roots when people describe a ‘call from god’ towards a particular walk of life that held was morally or socially significant (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997) or “divine inspiration to do morally responsible work” (Hall & Chandler, 2005, p.160). However, the religious connotations are becoming less pronounced over time. The religious meaning of calling meant being given a summons and choice. One could accept a calling and pursue work as an act of service, whereas the secular meaning of calling is more about one’s fulfilment. However, both approaches positively impact the world and act as an intrinsic motivation for doing the work for its own sake (Wrzesniewski et al., 2009).

Scholars have historically referred to a transcendental or spiritual summons (Dik & Duffy, 2009), linked to the older religious meaning of calling when it was a calling to God. But more recently, more secular definitions have prevailed towards a strong sense of inner direction. Internal desire, an inner voice and what one was meant to do are the common references (Elangovan et al., 2010).

It could be argued that the concept of a ‘calling’ within psychology is relatively new. As such, it is only natural for much academic debate to occur over terms and definitions. Much debate has occurred over semantics rather than scientific research (Duffy & Dik, 2013). However, it would be useful for scholars to put the debate aside and move on. Whether the drive one feels is God or an inner voice – it’s a drive. The theoretical model in 2018 (Duffy et al., 2018) and meta-analysis in 2019 (Dobrow Riza et al., 2019) provide a very useful consolidation of research and findings to date, providing a checkpoint in which to embark on what is hopefully a new wave of research around calling.

See Table one for a comparison of the religious versus secular views of calling.

A sense of contribution

The prosocial element defined within a calling is highlighted in the much earlier work of Austrian Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, studying man’s search for meaning, when he suggested the need for man to dedicate himself to a cause greater than himself (Frankl, 1959). The prosocial element was also a key element in the Self-Determination Theory by Ryan & Deci (2000), which suggests that a sense of contribution drives people. This wouldn’t necessarily have to be within a role that directly benefits society (Dik & Duffy, 2009), as long as it offered a sense of fulfilment, a sense of purpose and a mechanism to serve the greater good (Ahn et al., 2017). Perhaps most eloquently, a calling might be defined as “Where your deep gladness and the world’s hunger meet” (Hall & Chandler, 2005, p.161).

Career Change and Behaviour Models

Four models are of relevance to the concept of calling. A summary of the models is below; more details of each model can be found in Appendix 2.

-

- Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) – This framework aligns well with a sense of calling as it describes key components in people’s motivation. Finding a calling in one’s career is more likely when the career supports autonomy, allows for a sense of competence, and promotes a feeling of relatedness. So, employers or individuals seeking career interventions should find work aligned with their values, seek opportunities for mastery and connect their work with helping others.

- Career Construction Theory (M. Savickas, 2005) – This theory is useful for people seeking to identify their calling as it refers to ‘themes’ within work experience, allowing us to find our calling. The Career Construction Theory and Life Designing concepts advocate that individuals actively construct their careers based on personal agency, self-reflection, narrative construction, and collaboration.

- Life-Span, Life-Space Approach (Super, 1980) – Super’s framework is ideally suited for identifying when a calling will likely develop within an individual’s career. Like Savickas, The Life-Span, Life-Space approach suggests narratives and themes within an individual’s life that are related to several career development stages, growth, exploration, establishment and so on.

- Choosing a Vocation (Parsons, 1909) – This is not a framework per se but a defining piece of work in which much of the career advice industry seems to have been founded. It advocates understanding one’s skills and abilities and comparing this with job market knowledge. It highlights how conventional career advice will not necessarily allow someone to identify their calling since it focuses on ‘what career hole does my experience peg fit into’ rather than looking at intrinsic drive, prosocial motivation and meaning. What’s important to a person is more important to one’s

likes (Schippers & Ziegler, 2019). - Work as a Calling Model (Duffy et al., 2018) – The Work as a Calling theoretical model explains how perceiving work as a calling increases well-being at work. This represents a useful model and bookmark after around 20 years of research into calling. The model includes prerequisites of living a calling, the role of opportunity within the individual’s journey and positive and negative outcomes. As well as how the negative outcomes could be reduced.

Measurement Scales

Three measurement scales are relevant to the concept of calling. A summary of the models is below; more details about the scales are found in Appendix 2.

- The Work and Meaning Inventory (Steger et al., 2006) (Steger et al., 2012) – This tool measures meaning at work to help understand well-being and engagement. It is a useful scale to identify if someone would benefit from identifying their calling.

- The Work Preference Inventory (Amabile et al., 1994) – This tool is useful for identifying if someone prefers intrinsic or extrinsically motivated work. Those scoring high for the intrinsic drive would benefit from exploring a calling.

- Calling Scale Measure (Dobrow & Tosti-Kharas, 2011) – This scale identifies if people have a sense of calling in their work and can be used to help with employee engagement, well-being and fulfilment at work as well as being a diagnostic tool for those feeling existential angst.

Benefits of following a calling

The benefits of following a calling have been extensively researched and assessed. A high-level summary of the key findings is collated in Appendix 3. In short, people living their calling are happier, self-assured, healthier, more focused and productive, and more resilient. The same cannot be said for those searching for a calling (Dobrow Riza et al., 2019) who might be more indecisive (Duffy & Sedlacek, 2007) and those prevented from following their calling will feel frustration, disappointment and regret, which might ultimately impact their career success (Berg et al., 2010).

Like the extensive discussion on the definition of a calling, the same could be argued for the benefits. Viktor Frankl (1959) argued that we are driven by a ‘will to meaning’, an intrinsic drive to finding meaning in our life. And that if we don’t find it, it will cause us existential angst and ennui. There is plenty of research and evidence on calling’s benefits – but not about the issues that those benefits might address.

Future research should focus more on applying those benefits to improve mental health. For example, since following a calling is said to improve health and happiness, could interventions be designed to track the effectiveness of a calling for those unhealthy and unhappy? Frankl developed logotherapy, using meaning to address disorders, although his work was directed at overall life purpose and meaning rather than specifically a calling at work (Frankl, 1959). It is also worth exploring the impact of other personality traits on one’s predisposition to follow a calling; for example, it might be the case that those with a happier outlook on life were more likely to derive meaning from their work and, therefore, more likely to consider their work as a calling (Steger & Dik, 2009).

Similarly, more research is required on the social elements in the workplace, relationships, and culture on a sense of calling. It is argued that people can pursue a calling in their place of work if they are in an environment which fosters positive and mutually beneficial relationships and a flexible approach to the work identity (Cardador & Caza, 2012).

There are also many macroeconomic considerations to be explored with the benefits of following a calling:

- Modern economies have historically been built on extrinsic rewards, as we witness more drive for intrinsic rewards and balance (As witnessed by the great resignation after COVID (Morgan, 2022) ). What would happen if everyone followed their calling? How should organisations and economies adapt?

- As the world of work is disrupted by flexible working arrangements, artificial intelligence, and the consideration of universal income for some countries, how does calling come into play with people experiencing much more leisure time? (Susskind, 2020)

Challenges of following a calling

It could be argued that calling is a first-world phenomenon and a privilege. The assumption is that anyone with the luxury of pursuing a calling must check physiological and safety needs before pursuing a calling (Maslow, 1943), i.e. You would assume that putting a roof over one’s head and feeding the family would come before intrinsic needs and a sense of fulfilment.

Income level, education level and the demands of one’s family or responsibilities will hinder the pursuit of a calling (Duffy et al., 2018) (Dik & Duffy, 2009). A person’s current situation and psychological conditions must also be right (Ahn et al., 2017). The literature around calling mostly overlooks psychological conditions, a critical barrier to people pursuing their calling, especially in mid-life when perhaps they might already have an established career of some form that meets their extrinsic needs but leaves them feeling unfulfilled. A concept that does not apply to those leaving university and exploring the world of work for the first time. For example, the following fears and hindrances:

- The fear of failure – I have a perfectly good career; what if I pursue my calling and it doesn’t work out?

- The fear of the unknown – I’ll stick with my existing career because I don’t know what else to do even though I am unfulfilled.

- Imposter syndrome – What entitles me to pursue something else when I already have a job?

- Fear over what others may think – What will my parents, spouse and friends think of me leaving a perfectly good career to pursue a career with more meaning?

People exploring a career change, both in mid-career and young professionals joining the workforce, might experience societal pressures that may distract them from their true calling (Schippers & Ziegler, 2019). For example, this might include pursuing a career because their parents would approve, it would look good amongst peers, or it would look good on social media.

Just as following a calling has many benefits, it also has some potentially negative consequences due to those benefits. The benefit is spoilt if not managed properly. The sense of calling gives individuals a great sense of passion and purpose – but that same drive may result in workaholism as those following their calling gorge too much on work they love and might face exploitation by employers who might take advantage of this zest for the role (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009) (Cardador & Caza, 2012) (Duffy et al., 2018).

The pursuit of a calling

A person might proactively explore one’s interests and work history to explore a calling, an active approach. Or, using the older religious connotation of a calling, more passively wait for God to whisper something in one’s ear or for serendipity to strike. To pursue a calling, one must gather occupational information, self-reflect and assess the options available (Dik & Duffy, 2009).

People pursue a calling because they seek to change. They might be acting on a feeling of restlessness or, as Frankl described as ‘Sunday Neurosis’ – that feeling one has of ‘is this it?’ on a quiet Sunday afternoon before the busyness of the working week drowns out the true inner voice (Frankl, 1959). The change might also be thrust upon them as a life change, such as redundancy or a life event that suddenly changes one’s perspective, a jolt that makes them aware of their mortality.

The literature does not include enough research that analyses the tipping points that create this desire for change, especially for those seeking proactively. More research is required into the antecedents that lead to someone wanting to change and follow a calling (Dobrow Riza et al., 2019) (Duffy & Dik, 2013). It could be argued that the development of a calling could be linked to a person’s ability to make sense of their experiences (Ahn et al., 2017). In this case, the sense of calling does not come as a jolt but as a creeping sense of desire as one ages and processes their experiences.

Major events such as 9/11 or COVID have led employees to reflect on their values and reassess what they do for a living. Some opt for more prosocial work (Grant & Wade-Benzoni, 2009). Similarly, challenging experiences at work may lead to people pursuing a calling, with negative work experiences helping shape their motivation (Ahn et al., 2017).

The meaning of work is said to be shaped by social interactions and shared narratives. So previous work experiences are understood in the context of interactions with others. This means that organisations have a hand in shaping meaningful work by creating environments that help create positive relationships, open communication and the sharing of stories. So the people we work with could potentially help us interpret meaning from our work -(Wrzesniewski et al., 2003).

Lysova et al. (2019) expand on this and suggest meaningful work includes individual factors, such as alignment with values; interpersonal factors, such as our social connections at work; and organisational factors, such as practices, culture, and leadership. Employers should be interested in an individual’s sense of calling as it relates directly to their performance (Lee et al., 2018) (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003).

Techniques for pursuing a calling.

The literature recommends several different techniques to use when pursuing a calling. All of these are designed to clarify identity, bolster self-concept, and explore opportunities:

- Just get started – On starting the pursuit, any action appears beneficial. Any experience of a new career in the right direction generates positive emotions and more self-confidence, which further builds momentum in one’s chosen direction – (Murtagh et al., 2011) (Dik & Steger, 2008)

- In-depth self-exploration is exploring one’s best possible self, values, strengths, and passions. Reflect on gut feelings and intuition, which may point towards career options (Ahn et al., 2017) (Murtagh et al., 2011) (Dik & Duffy, 2009) (Schippers & Ziegler, 2019). Use written exercises including written goals (Dik & Duffy, 2009) (Dik & Steger, 2008) (Brown et al., 2003)

- Make sense of past experiences and career-related emotions – Assessing the source and strength of any existing sense of calling. Positive emotions can strengthen commitment and motivate action (Ahn et al., 2017) (Murtagh et al., 2011) (Adams, 2012).

- Help others – Once life purpose or meaning is addressed – connect with larger societal or community needs. Identify where they perceive themselves helping (Dik & Duffy, 2009) (Adams, 2012).

- Build Social Support – Have a dialogue with others (Dik & Steger, 2008) (Elangovan et al., 2010)

- Work with Up-to-date occupational information (Dik & Steger, 2008) (Brown et al., 2003)

- Be self-motivated – (Ryan & Deci, 2000) (Schippers & Ziegler, 2019)

- Have an openness to new directions (Duffy & Dik, 2013)

Summary – Exploring Calling

This study has explored the concept of a calling at work. The definition of calling across several decades of research was reviewed; this included comparing calling to terms such as job or career and the connection between calling and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The constituent parts that make up a calling were discussed: the inner conviction to pursue a particular direction, the prosocial or the means of contributing towards community or society, as well as a path that is aligned to one’s values, strengths, and issues that one feels are important.

It was identified that career models could help us understand people’s motivation and behaviour about a sense of calling. Measurement scales can help assess someone who might benefit from finding their calling. This study has explored techniques for pursuing a calling. The most significant of which was in-depth self-exploration and making sense of past experiences and career-related emotions from the past.

The benefit of following a calling are individuals being happier, self-assured, healthier, more focused and productive at work and more resilient. This study has summarised that the literature in the field has dealt too long with definitions and benefits. It should now move on to the application of those benefits and how they might positively impact well-being in the workplace and people’s careers.

Future research should explore the link between relationships at work and culture in the workplace as it relates to calling to delve into how employers can create environments that create a sense of calling or help employees explore their calling resulting in greater well-being and productivity. Similarly, the psychological barriers preventing individuals from pursuing a calling in mid-career should also be explored further.

When it comes to the pursuit of a calling, one can do that actively or passively. More research must be conducted for those doing it actively to establish the tipping points that stimulate people to act on their calling. Antecedents required to generate a sense of calling should be investigated, and if a sense of calling comes from making sense of one’s experiences, then what experiences impact a sense of calling most?

Research Aims

This study aims to enhance the knowledge around calling at work by focussing on identifying a calling for mid-career professionals, the pursuit of a calling, and its overall effects. Specifically, this will build on how the benefits of following a calling might be applied to impact well-being in the workplace and people’s careers, the link between calling and relationships at work, the psychological barriers preventing individuals from following a calling and the antecedents required before an individual begins to act.

As a result of this conducting this research, the aim is to answer the following questions:

- How can the benefits of following a calling be applied to improve workplace conditions and outcomes?

- What psychological barriers prevent mid-career professionals from identifying and following their calling at work?

- What antecedents, such as personal characteristics, experiences, or environmental factors, are required before an individual begins to pursue their calling?

Literature review for University of East London Masters course in Business Psychology. Martin Thompson, Summer 2023.

References – Exploring Calling

- Adams, C. M. (2012). Calling and Career Counseling With College Students: Finding Meaning in Work and Life. Journal of College Counseling, 15(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00006.x

- Ahn, J., Dik, B. J., & Hornback, R. (2017). The experience of career change driven by a sense of calling: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.003

- Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., & Tighe, E. M. (1994). The Work Preference Inventory: Assessing Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivational Orientations.

- Berg, J. M., Grant, A. M., & Johnson, V. (2010). When Callings Are Calling: Crafting Work and Leisure in Pursuit of Unanswered Occupational Callings. Organization Science, 21(5), 973–994. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0497

- Brown, S. D., Ryan Krane, N. E., Brecheisen, J., Castelino, P., Budisin, I., Miller, M., & Edens, L. (2003). Critical ingredients of career choice interventions: More analyses and new hypotheses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(3), 411–428.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00052-0 - Bunderson, J. S., & Thompson, J. A. (2009). The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings, and the Double-edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(1), 32–57. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2009.54.1.32

- Cardador, M. T., & Caza, B. B. (2012). Relational and Identity Perspectives on Healthy Versus Unhealthy Pursuit of Callings. Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 338–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436162

- Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2009). Calling and Vocation at Work: Definitions and Prospects for Research and Practice. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(3), 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008316430

- Dik, B. J., & Steger, M. F. (2008). Randomized trial of a calling-infused career workshop incorporating counselor self-disclosure. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.04.001

- Dobrow Riza, S., Weisman, H., Heller, D., & Tosti-Kharas, J. (2019). Calling Attention to 20 Years of Research: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Calling. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2019(1), 12789. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.199

- Dobrow, S. R., & Tosti-Kharas, J. (2011). CALLING: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A SCALE MEASURE. Personnel Psychology, 64(4), 1001–1049. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01234.x

- Duffy, R. D., Bott, E. M., Allan, B. A., Torrey, C. L., & Dik, B. J. (2012). Perceiving a calling, living a calling, and job satisfaction: Testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026129

- Duffy, R. D., & Dik, B. J. (2013). Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.006

- Duffy, R. D., Dik, B. J., Douglass, R. P., England, J. W., & Velez, B. L. (2018). Work as a calling: A theoretical model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(4), 423–439.

https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000276 - Duffy, R. D., Dik, B. J., & Steger, M. F. (2011). Calling and work-related outcomes: Career commitment as a mediator. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78(2), 210–218.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.013 - Duffy, R. D., & Sedlacek, W. E. (2007). The presence of and search for a calling: Connections to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(3), 590–601.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.03.007

Elangovan, A. R., Pinder, C. C., & McLean, M. (2010). Callings and organizational behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 428–440.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.10.009 - Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s Search For Meaning.

- Grant, A. M., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2009). THE HOT AND COOL OF DEATH AWARENESS AT WORK: MORTALITY CUES, AGING, AND SELF-PROTECTIVE AND PROSOCIAL MOTIVATIONS. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 600–622. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2009.44882929

- Hagmaier, T., & Abele, A. E. (2012). The multidimensionality of calling: Conceptualization, measurement and a bicultural perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 39–

51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.04.001 - Hall, D. T., & Chandler, D. E. (2005). Psychological success: When the career is a calling. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.301

- Hill, P. L., & Turiano, N. A. (2014). Purpose in Life as a Predictor of Mortality Across Adulthood. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1482–1486.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614531799 - Hirschi, A. (2012). Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(3), 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028949

- Kang, Y., Kim, E., Strecher, V. J., & Falk, E. B. (2019). Purpose in Life and Conflict-Related Neural Responses During Health Decision-Making.

- Kim, E. S., Strecher, V. J., & Ryff, C. D. (2014). Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(46), 16331–

16336. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414826111 - Lee, A. Y.-P., Chen, I.-H., & Chang, P.-C. (2018). Sense of calling in the workplace: The moderating effect of supportive organizational climate in Taiwanese organizations. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(1), 129–144.

https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.16 - Lysova, E. I., Allan, B. A., Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Steger, M. F. (2019). Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 374–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.07.004

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation.

- Morgan, K. (2022, 08). The Great Resignation was triggered by the pandemic – so why aren’t resignations slowing down now as it wanes? BBC Worklife. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220817-why-workers-just-wont-stop-quitting

- Murtagh, N., Lopes, P., & Lyons, E. (2011). Decision making in voluntary career change. The Career Development Quarterly, 59(3), 249–263.

- Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Pratt, M., & Ashforth, B. (2003). Fostering Meaningfulness in Working and at Work. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline (pp. 309–327). Berrett-Koehler.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist.

- Savickas, M. (2005). CAREER CONSTRUCTION THEORY.

- Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J.-P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., Soresi, S., Van Esbroeck, R., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for

career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004 - Schippers, M. C., & Ziegler, N. (2019). Life Crafting as a Way to Find Purpose and Meaning in Life. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2778. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02778

- Steger, M. F., & Dik, B. J. (2009). If One is Looking for Meaning in Life, Does it Help to Find Meaning in Work? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1(3), 303–320.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01018.x - Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring Meaningful Work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160 - Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

- Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16(3), 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

- Susskind, D. (2020). A world without work. Penguin.

- Vondracek, F. W. (1992). The Construct of Identity and Its Use in Career Theory and Research. The Career Development Quarterly, 41(2), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1992.tb00365.x

- Wrzesniewski, A., Dekas, K., & Rosso, B. (2009). Callings. In Encylopedia of Positive Psychology. Blackwell.

- Wrzesniewski, A., Dutton, J., & Debebe, G. (2003). Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 25, 93–135.

- Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, Careers, and Callings: People’s Relations to Their Work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2162

Appendices

Appendix 1 – Career Change Models

Self-Determination Theory, (Ryan & Deci, 2000)

Self-determination theory is a framework for understanding human motivation. The theory suggests that three psychological needs drive people’s motivation:

- Autonomy – The need to feel like we have control over our own choices and can make choices aligned with our values.

- Competence – The need to feel effective and master challenges.

- Relatedness – The need to feel connected to others, feel part of a group and feel like you are contributing to something more than your own needs.

When these three needs are met, one feels “self-determined”, motivated, and has a sense of well-being and growth. When these needs are unmet, people can experience lower motivation and a lower sense of well-being.

Related specifically to a calling:

- Autonomy: When people perceive their career choice as coming from their personal interests, values, and desires rather than external pressures or expectations, they experience higher job satisfaction, well-being, and motivation. They’re more likely to see their career as a calling.

- Competence: When people feel they’re good at what they do and can handle their job’s challenges, they’re more likely to find their work meaningful and satisfying. If a person’s career allows them to use and develop their skills effectively, they’re more likely to view it as a calling.

- Relatedness: Careers that enable people to connect with others, contribute to society, or feel part of a larger mission can satisfy the need for relatedness. When people feel their work contributes to something beyond themselves, they’re more likely to view it as a calling.

In summary, finding a calling in one’s career is more likely when the career supports autonomy, allows for a sense of competence, and promotes a feeling of relatedness.

According to Self-Determination Theory, employers and individuals seeking career change should identify and find work aligned with values, seek opportunities for Mastery and connect their work to helping others.

Career Construction Theory, (M. Savickas, 2005)

Career Construction Theory by Mark Savickas recognises that people’s careers are no longer a lifetime commitment to one employer, as might have happened in the past. But instead views employees as selling services and skills to a set of employers with various requirements. Similar to (Super, 1980), The employee constructs their career based on a salary negotiated but also the potential meaning the role brings to their life, the advancement opportunities, the balance with life outside work, etc.

Savickas argues that through subjective career experiences, employees can portray a story of their life, a theme, and its meaning. Weaving in memories, present experiences, and future aspirations. Through this theme, an individual can express their personality at work. As their self-concept evolves throughout their life, so can their career.

Later, Savickas and colleagues explored the idea of “Life Designing” as a means for individuals to shape their careers based on their changing interests. (M. L. Savickas et al., 2009).

Several key principles and processes are proposed that underpin the life-designing approach:

- Life as a design project: Viewing one’s life and career as an ongoing design project that requires active engagement, exploration, and experimentation. This perspective encourages individuals to take ownership of their career development and continuously refine their goals and strategies.

- Narrative construction: Recognizing the role of personal storytelling in making sense of one’s experiences, strengths, and aspirations. Constructing narratives allows individuals to create meaning and coherence in their career journeys.

- Co-construction and collaboration: Emphasizing the importance of social connections and collaborative relationships in career development. Engaging with others, such as mentors, peers, and professionals, can provide valuable support, guidance, and growth opportunities.

- Possibility thinking: Encouraging individuals to expand their thinking and consider various career possibilities. This involves exploring emerging fields, embracing change, and cultivating a mindset of adaptability and resilience.

In summary, life designing is an approach to career construction in the 21st century. It advocates for a proactive and flexible approach to career development, where individuals actively construct their careers based on personal agency, self-reflection, narrative construction, and collaboration.

Like Savickas, (Vondracek, 1992) suggests that the construct of identity can be used to track career development processes and outcomes. Vondracek argues that identity shapes individuals’ career choices, vocational development, and career-related behaviours. He highlights that a strong, well-developed sense of identity can positively influence career decision-making, goal-setting, and overall career satisfaction.

A Life-Span, Life Space Approach to Career Development, by (Super, 1980)

“A Lifespan, Life-Space Approach to Career Development” by Donald E. Super, published in 1980, presents a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding and facilitating career development throughout an individual’s lifespan. Super’s approach considers various factors such as personal characteristics, social roles, and the influence of the environment.

According to Super, the concept that career development is not a linear process but rather a dynamic and evolving journey that occurs across one’s entire life and extends beyond the boundaries of work. Super argues that numerous factors influence career development, including personal interests, abilities, values, aspirations, and social, economic, and cultural contexts.

Super argues that individuals go through several stages in their career development, which he refers to as the “lifespan” perspective. These stages include growth, exploration, establishment, maintenance, and disengagement. Each stage represents different developmental tasks and challenges that individuals encounter as they progress through their careers. The stages allow for the development of the self-concept, so as the individual becomes more experienced, they develop a more mature self-concept.

Super also emphasises the importance of the “life-space” aspect of career development, which involves the integration of multiple life roles and domains. He suggests that individuals have various roles, such as worker, family member, and community participant, and these roles interact and influence each other. Understanding and balancing these different roles is crucial for achieving career satisfaction and overall life satisfaction. Super provides a framework that can be used to guide career counselling and intervention programs. It highlights the significance of considering an individual’s unique

characteristics, values, and life circumstances when assisting them in their career development journey.

Choosing a Vocation (Parsons, 1909)

“Choosing a Vocation” by Frank Parsons is a seminal work in the field of career counselling, written in 1909. It is often credited as being the foundation for the discipline of vocational guidance.

In essence, the book suggests three key principles for effective career decision-making:

- Self-understanding: Parsons emphasised the importance of understanding one’s own abilities, interests, ambitions, resources, limitations, and the causes and effects of

these factors. He suggested that a clear self-understanding is the first step towards making sound vocational decisions. - Knowledge of jobs, skills, and the job market: The second principle revolves around the importance of acquiring a deep knowledge of different vocations, their required skills, and the conditions and compensations they offer. This knowledge is crucial in helping individuals assess their suitability for various jobs.

- True reasoning on the relations of these two groups of facts: After acquiring a clear understanding of oneself and the job market, the third principle involves the logical

and reasoned matching of these two sets of facts. Parsons asserted that making a rational match between personal attributes and job requirements would lead to more satisfying and productive career choices.

Parsons’ book is foundational to the field of vocational guidance and laid the groundwork for many subsequent theories and models in career counselling. His ideas continue to be relevant in the present day, given that career decision-making is a vital part of everyone’s life.

Work as a Calling Model by (Duffy et al., 2018)

The Work as a Calling theoretical model explains how perceiving work as a calling explains increased well-being at work. This represents a useful model and bookmark after around 20 years of research into calling. The model includes prerequisites of living a calling, the role of opportunity within the individual’s journey and positive and negative outcomes. As well as how the negative outcomes could be reduced.

Appendix 2 – Measurement Scales

The Work and Meaning Inventory by (Steger et al., 2006) (Steger et al., 2012)

Steger, Dik and Duffy argue that measuring meaning at work is important to understand employee well-being and engagement. The Work and Meaning Inventory is a self-report questionnaire that records meaning across four scales:

- Personal Development: This scale assesses how individuals perceive their work as contributing to personal growth, learning, and development.

- Purpose: This scale measures the degree to which individuals feel that a sense of purpose drives their work and contributes to something larger than themselves.

- Episodic Experiences: This scale focuses on the quality of specific work experiences that are meaningful and memorable, capturing the presence of events or moments that

enhance a sense of meaningful work. - Personal Expressiveness: This scale examines how individuals feel their work allows them to express their unique values, strengths, and identities.

The authors propose that their meaning measurement scale provides a tool to be used for research, career counselling and organisational interventions.

The Work Preference Inventory by (Amabile et al., 1994)

The Work Preference Inventory assesses an individual’s preferences regarding intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

The inventory consists of two scales.

1. Intrinsic Orientation: This scale measures the degree to which individuals are motivated by internal factors, such as finding the work inherently interesting, enjoyable, and personally fulfilling. It assesses the extent to which individuals derive satisfaction from the work itself rather than external rewards or outcomes.

2. Extrinsic Orientation: This scale assesses the degree to which individuals are motivated by external factors, such as tangible rewards (e.g., salary, promotions) and social recognition. It captures the extent to which individuals are driven by external outcomes rather than the inherent enjoyment or fulfilment of the work.

The authors discuss the practical implications of the Work Preference Inventory, highlighting how it can be utilised in research and applied settings to understand individuals’ motivational orientations and tailor interventions accordingly. They also note the potential for using the inventory to assess changes in motivational orientations over time.

Calling Scale Measure by (Dobrow & Tosti-Kharas, 2011)

The calling scale measure identifies if individuals have a sense of calling in their work. The scale consists of three dimensions.

- Perceiving a Calling: This dimension assesses how individuals perceive their work as a calling and experience a deep sense of meaning, purpose, and significance in what they do. It captures the belief that their work is essential to their identity and reflects their core values and passions.

- Living a Calling: This dimension focuses on the behavioural aspect of calling, examining how individuals actively live out their calling in their work. It assesses behaviours such as going above and beyond, seeking opportunities for growth and development, and using their work to impact others positively.

- Aligning with a Calling: This dimension examines the fit between individuals’ work and their calling. It assesses how individuals perceive their work as congruent with their calling, evaluating factors such as skill utilisation, job fit, and alignment with personal values and interests.

The authors suggest that the scale can be used to promote individuals’ engagement, well-being, and fulfilment in their work.

Appendix 3 – Benefits of Living a Calling

Happier

Those following their calling are happier, more committed to the work and most engaged, with higher intrinsic motivation. Promotes a sense of social connection via their prosocial contribution. (Duffy et al., 2011) (Duffy et al., 2018) (Ahn et al., 2017) (Duffy & Sedlacek, 2007) (Elangovan et al., 2010)

Self-Assured

When psychological needs are met at work – people report higher self-esteem and less anxiety. More peaceful, balanced, and stable. Strong sense of passion, vigour and feelings of fulfilment. (Steger & Dik, 2009), (Hall & Chandler, 2005), (Berg et al., 2010) (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009) (Ahn et al., 2017) (Hirschi, 2012)

Healthier

Being in a calling related to better mental and physical health, fewer days off work, purposeful individuals live longer, more proactive in seeking out preventative healthcare options, less conflict-related regulatory burden during health decision-making – (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997) (Hill & Turiano, 2014) (Kim et al., 2014) (Kang et al., 2019)

Focussed and Productive

Greater Job Satisfaction, Life satisfaction and Success at Work, greater commitment to their profession, more decided and comfortable in their career choices, greater vocational self-clarity, attributed greater importance to their careers, and less likely to withdraw from their job. – (Duffy et al., 2018) (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009), (Duffy et al., 2012), (Dik & Duffy, 2009) (Steger & Dik, 2009) (Hirschi, 2012) (Duffy & Sedlacek, 2007)

More Resilient

Greater self-concept clarity, use of problem-focussed coping, less stress, depression and avoidance coping, less likely to experience conflict between work and non-work – (Dik & Duffy, 2009) (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009) (Hirschi, 2012) (Elangovan et al., 2010)